Hamilton's Mangrove Deforestation Research Aids Global Preservation

SALISBURY, MD---A global database of mangrove forests co-created by Dr. Stuart Hamilton of Salisbury University’s Geography and Geosciences Department could aid coastal preservation efforts and impact climate policy discussions worldwide.

SALISBURY, MD---A global database of mangrove forests co-created by Dr. Stuart Hamilton of Salisbury University’s Geography and Geosciences Department could aid coastal preservation efforts and impact climate policy discussions worldwide.

Mangroves store high densities of carbon and when they are deforested it, harmfully, is emitted into Earth’s atmosphere, Hamilton explained.

To help curb this, he and his colleague, Dr. Daniel Friess of the National University of Singapore, set out to determine just how much carbon mangroves contain – and how much is being lost. The results, they believe, can be used for decision-making by municipalities and environmental benchmarking by international organizations.

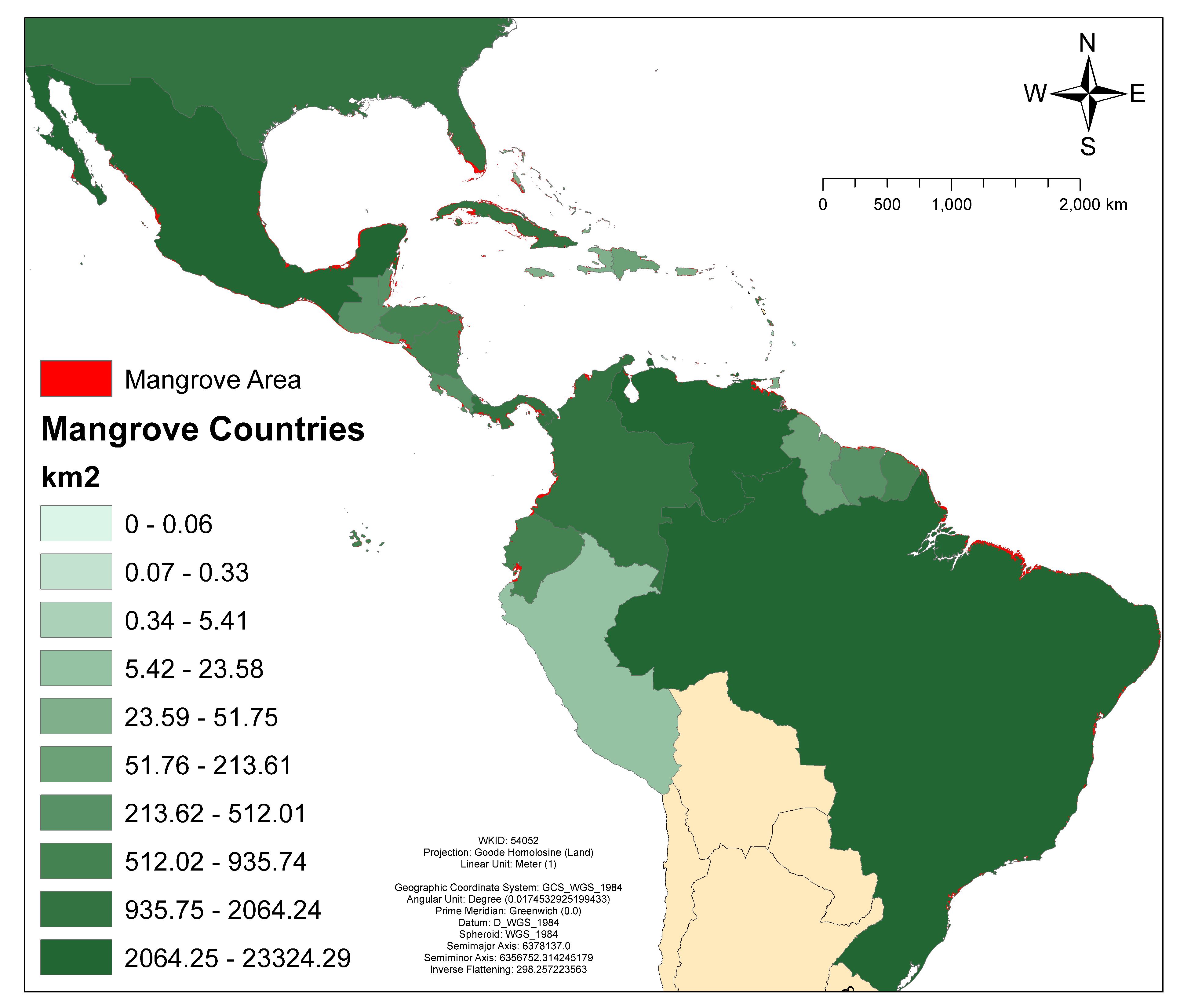

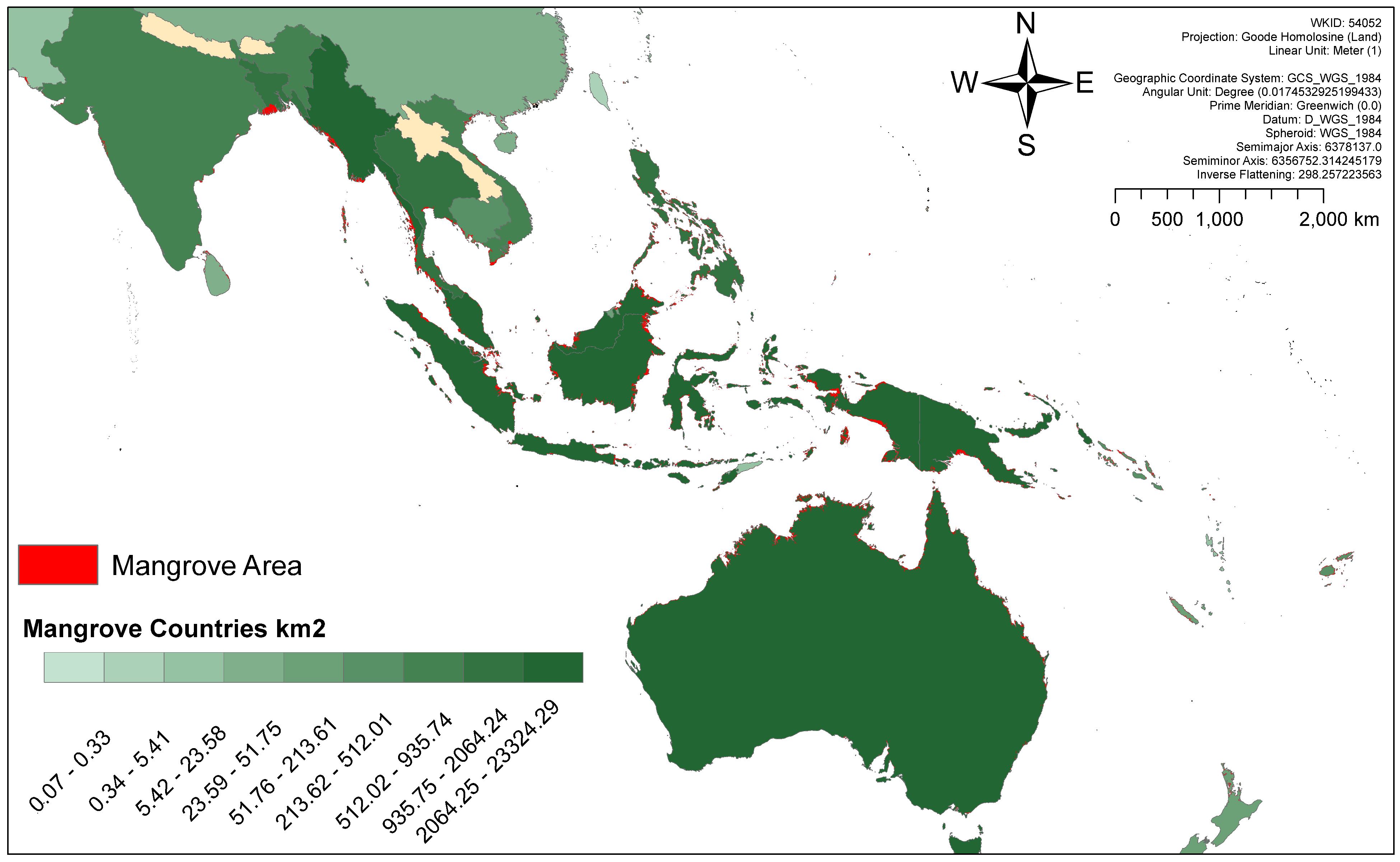

The researchers synthesized multiple satellite datasets on forest, mangrove and land covers worldwide, combining them into one Global Mangrove Carbon Stocks Database. This will allow other officials, researchers and non-governmental organizations to monitor loss rates for sites of interest almost anywhere globally, Hamilton said.

Their results recently were published recently in Nature Climate Change, a journal dedicated to such research and implications on economies, policies and the world. It also garnered attention from Mongabay, a global environmental news site; Climate Brief, a United Kingdom-based website; and other outlets from South Africa to Asia.

Their results recently were published recently in Nature Climate Change, a journal dedicated to such research and implications on economies, policies and the world. It also garnered attention from Mongabay, a global environmental news site; Climate Brief, a United Kingdom-based website; and other outlets from South Africa to Asia.

In addition, Hamilton said the data is being used as a bio-indicator by the United Nations Environment World Conservation Monitoring Centre to see which nations are on track to meet their Aichi 2020 biodiversity targets developed by the Convention on Biological Diversity.

“Dr. Hamilton’s work is a big deal,” said Dr. Michael Scott, interim dean of SU’s Richard A. Henson School of Science and Technology. “He is making an impact on efforts to save our planet.”

In creating the database, Hamilton and Friess found that worldwide, mangroves stored 4.19 billion metric tons of carbon in 2012 (equivalent to the U.S. and China’s annual emissions combined). This is two percent less than the amount stored in 2000, and the figure likely has dropped further to 4.16 billion metric tons in 2017. This lost carbon translates to some 317 million tons of CO2 emissions per year (equivalent to the emissions of 67.5 million passenger vehicles annually in the U.S.).

Mangroves store carbon mostly in their underlying soil as well as in the living vegetation, Hamilton said, adding that they can hold up to four times as much as land-based forests and rainforests. They also are important, he said, because they provide critical ecosystem services like erosion control and flood mitigation, and serve as habitats for fish, birds and other species.

Mangroves store carbon mostly in their underlying soil as well as in the living vegetation, Hamilton said, adding that they can hold up to four times as much as land-based forests and rainforests. They also are important, he said, because they provide critical ecosystem services like erosion control and flood mitigation, and serve as habitats for fish, birds and other species.

Indonesia, Brazil, Malaysia and Papua New Guinea have half of the global total of mangroves, but Southeast Asia also has some of the highest rates of deforestation. Some are cleared for charcoal, palm oil plantations or aquaculture (seaweed, shrimp and fish). They also can be drowned by rising seas and starved by dam building.

But, Hamilton said, now having a way to rapidly assess mangrove cover and identify at-risk areas, especially at local management levels, is critical. For more information, call 410-543-6030 or visit the 成人抖阴website at www.salisbury.edu.